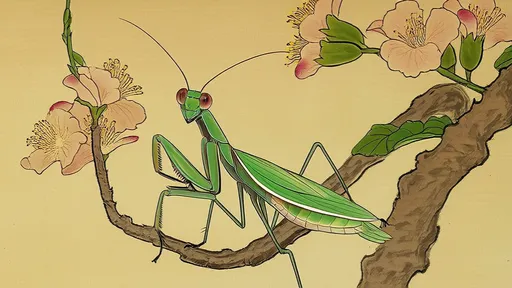

The delicate brushwork of a cicada's translucent wings, the precise articulation of a mantis's spiked forelegs—such details in the paintings of Emperor Huizong's court reveal more than just artistic mastery. They unveil an entire philosophy of observation that transformed Chinese art during the Northern Song Dynasty. These seemingly insignificant insects, immortalized in ink and color on silk, hold the key to understanding the revolutionary approach to life drawing that emerged from the Imperial Painting Academy under Huizong's obsessive patronage.

Modern viewers might mistake these works for mere decorative motifs or symbolic gestures, but contemporary records and the paintings themselves tell a different story. The emperor's famous «Cicada on Banana Leaf» and «Mantis Behind a Plantain» represent the culmination of a systematic study of nature that bordered on scientific inquiry. Court artists didn't just sketch these creatures—they lived with them in specially designed gardens, observed their behaviors through different seasons, and documented their anatomical structures with an accuracy that would make Renaissance naturalists nod in approval.

What made Huizong's approach radical was its departure from earlier traditions of copying masterworks. The emperor mandated direct observation as the foundation of artistic training, instituting what we might now call an «empirical turn» in Chinese painting. His 1104 reform of the Imperial Academy established rigorous examinations where candidates had to depict subjects like birds, flowers, and insects from life rather than memory or existing compositions. This created an entire generation of painters who could render the exact number of segments in a mantis's antennae or the veining pattern unique to each cicada species.

The technical precision achieved in these works wasn't coldly mechanical—it pulsed with vitality. Artists learned to capture the moment before movement: the slight bend in a mantis's knee that precedes its lethal strike, the tension in a cicada's wings milliseconds before flight. This required not just anatomical knowledge but profound patience. Historical accounts describe painters spending entire days motionless in gardens, waiting for the perfect natural pose. The resulting works achieve what Huizong called «transmission of divine resonance»—an energy that makes painted insects seem ready to spring off the silk eight centuries later.

Recent scholarship has uncovered how these insect studies served as visual training manuals for larger compositions. The same principles used to render a mantis's segmented abdomen were scaled up to depict the overlapping plates of scholars' robes or the layered petals of peonies. This explains why Huizong insisted even landscape painters master insect painting—the discipline cultivated an eye for microscopic detail that informed macroscopic compositions. The emperor's own calligraphy, with its precisely modulated brushstrokes, shows this influence; each character's strokes resemble the jointed limbs of his beloved insects.

The political dimension of this artistic program shouldn't be overlooked. By focusing on nature's smallest creatures, Huizong subtly communicated his empire's omniscience—nothing escaped the imperial gaze, not even a cicada hidden among leaves. The paintings also embodied Confucian ideals through their meticulous ordering of nature's chaos. When a mantis in a Huizong-era painting raises its forelegs in what appears to be a martial pose, it's simultaneously an accurate behavioral study and a metaphor for loyal ministers defending their ruler.

Modern techniques like macro-photography have revealed astonishing details invisible to the naked eye. In «Cicada on Banana Leaf», the artist depicted microscopic hairs on the insect's thorax that catch morning dew—a detail observable only through magnified study. This suggests the use of early optical aids like water-filled glass spheres, predating Western lens technology by centuries. The paintings thus become encrypted records of Song Dynasty proto-scientific inquiry, their aesthetic beauty masking cutting-edge observational methods.

The legacy of Huizong's insect studies extends far beyond their initial context. They influenced later «bird-and-flower» painting traditions and even found echoes in Japanese Edo-period nature prints. More profoundly, they established an artistic epistemology where truth emerged from disciplined looking rather than inherited convention. In an age when digital tools dominate visual culture, these eight-hundred-year-old insects still challenge us to see the world anew—one precise, patient observation at a time.

Perhaps the ultimate testament to their power lies in their survival. While wars destroyed Huizong's palaces and scattered his collections, these fragile-seeming paintings of delicate creatures endured. The very subjects the emperor chose—cicadas symbolizing rebirth in Chinese culture, mantises representing vigilance—became unwitting prophecies of his art's immortality. Today, as conservators peer through microscopes at the brushstrokes beneath these insects' wings, they're not just preserving art. They're continuing the emperor's original mission: uncovering nature's secrets through the marriage of unblinking observation and transcendent skill.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025