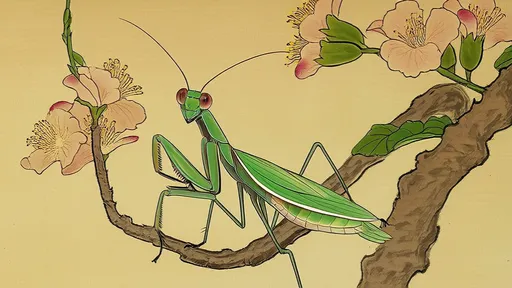

The metamorphosis of Gregor Samsa into a monstrous vermin remains one of the most haunting openings in literary history. Franz Kafka’s "The Metamorphosis" is not merely a tale of bodily transformation but a piercing allegory of alienation in modern society. Written in 1915, the novella captures the existential dread of an individual reduced to insignificance by the machinery of capitalism, familial expectations, and bureaucratic absurdity. Over a century later, Kafka’s vision of dehumanization resonates with unsettling clarity in our hyper-connected yet emotionally fragmented world.

Gregor’s transformation is instantaneous, but his alienation is not. Before becoming an insect, he was already a cog in an oppressive system—a traveling salesman burdened by debt, laboring under the weight of providing for his family. His humanity was eroded long before his body betrayed him. Kafka’s genius lies in rendering the psychological reality of alienation literal: Gregor’s grotesque form mirrors how society perceives (and discards) those who cease to be economically useful. The family’s revulsion, their eventual neglect, and their quiet relief at his death lay bare the transactional nature of human relationships in a capitalist framework.

The modern workplace, with its cult of productivity and performative hustle, mirrors Gregor’s pre-insect existence. Employees are reduced to metrics, their worth measured by output rather than intrinsic humanity. The rise of gig economies and precarious labor conditions exacerbates this alienation—workers, like Gregor, scuttle from one task to another, their identities flattened into functional roles. Burnout, a term absent in Kafka’s time, is now the defining malaise of our era. The insect shell is merely a metaphor for what many already feel: invisible, disposable, and grotesquely disconnected from their own lives.

Familial bonds, too, are scrutinized under Kafka’s unflinching gaze. Gregor’s sister Grete initially cares for him, but her compassion withers as his utility diminishes. The family’s eventual rejection is not born of malice but of necessity—a survival instinct in a society that prizes economic contribution above all else. This dynamic finds echoes today, where caregiving is often outsourced, and the elderly or infirm are sequestered in facilities, their dependence framed as a burden. The nuclear family, idealized as a sanctuary, is revealed as another site of conditional love and unspoken contracts.

Technology, ostensibly designed to connect us, has deepened the paradox of isolation. Social media platforms demand constant self-commodification; we curate personas as meticulously as Gregor’s family hides his existence from their lodgers. The more "connected" we become, the more we experience what sociologists call "liquid loneliness"—a pervasive sense of isolation amidst digital overcrowding. Kafka’s cockroach, shunned in a crowded apartment, is the spiritual ancestor of the modern individual scrolling through endless feeds, yearning for authentic connection yet incapable of achieving it.

Bureaucracy, another Kafkaesque nightmare, thrives in contemporary life. Endless paperwork, automated customer service loops, and algorithmic decision-making reduce individuals to case numbers. Gregor’s inability to communicate with his family after his transformation mirrors the frustration of navigating opaque systems—whether healthcare, immigration, or corporate HR. The inhumanity of these structures is not a bug but a feature; they operate on the assumption that human complexity is an inconvenience to efficiency.

Yet Kafka’s work is not wholly nihilistic. Gregor’s death, while tragic, liberates his family from the weight of his existence. In a grotesque twist, his sacrifice enables their rebirth—his sister blossoms, his parents regain vitality. This ambivalence forces readers to confront uncomfortable questions: Is alienation the price of societal functioning? Can compassion coexist with survival? The text offers no easy answers, but its power lies in the questions it provokes.

Contemporary artists continue to grapple with these themes. Films like "The Lobster" (2015) and novels such as Ottessa Moshfegh’s "My Year of Rest and Relaxation" explore voluntary and involuntary withdrawal from society. The rise of "quiet quitting" and the Great Resignation movement signal a collective awakening to the dehumanizing demands of late-stage capitalism. Like Gregor, many are choosing to opt out—not through physical transformation but by rejecting the scripts handed to them.

Kafka’s nightmare vision endures because it was never just about a man turning into a bug. It was about the bug that was always there—the creeping sense of otherness, the fear of becoming obsolete, the terror of being seen in one’s naked vulnerability. In an age of AI, climate crisis, and geopolitical upheaval, the specter of metamorphosis looms larger than ever. Perhaps we are all Gregor now, whispering through chitinous mouths, waiting to see if anyone will hear.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025